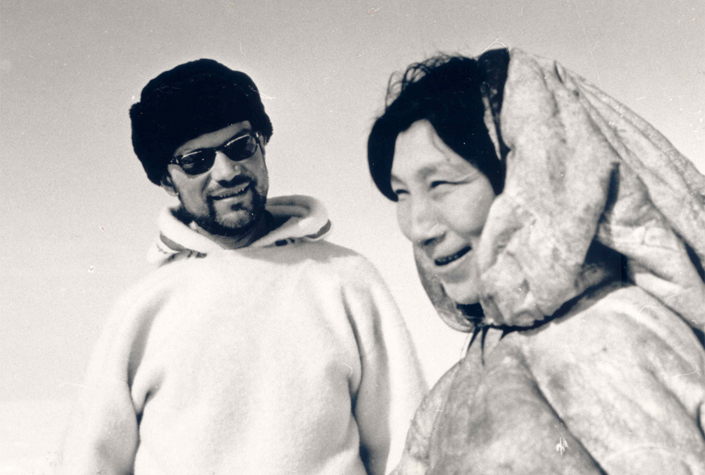

by Asen Balikci

“Visual anthropology started with the legacy of Boas and the grand design of establishing ethographic records, truthful records of enduring value, with the help of modern technological aids. It continued with Margaret Mead and the use of film as an integral part of any anthropological research Programme. At the present time, ethnographic film is made for audiences which have grown increasingly large. The anthropologist has also changed vocation: in the beginning he considered himself merely an objective recorder; he later came to think of himself as an analytical scientist; now, he, or she, is only too painfully aware of the danger of becoming an unconscious ideological manipulator.

Today, it seems that some formats and approaches suffer from neglect. There are no new projects similar in scope to the Bushmen, Yanomamo or Netsilik series. The tradition of prolonged involvement in a single culture area seems to have been lost, at least temporarily. There are very few attempts to use the camera in anthropological field research. The Smithsonian and Göttingen film archives are rarely consulted for analytic purposes. Although much experimental filming is going on there is a painful feeling that presently nobody can do better than Gardner’s mythopotics, MacDougall’s observational genre of LIewelyn-Davies’ reflexive style. The highly successful television format in Britain does not seem to be stimulated by much experimental work. In a sense, television here seems to be in competition with nothing more than itself.

Visual anthropology however is still in its infancy, trying hard to establish its epistemological validity. It should not be perceived as being in competition with mainstream analytical anthropology; rather, it should be seen as complementary and its practitioners should see to make the best possible use of its particular Potential for understanding the human condition. New approaches and new fields of interest are currently being developed, such as anthropological analyses of feature and documentary films. The study of popular imagery or the examination of native aesthetic styles. Third World institutions assemble video records of minority cultures with the direct help of indigenous groups concerned about cultural preservation. Encapsulated societies increasingly consider video-making as the starting point of ethnic self-assertion and political liberation. Visual anthropologists are becoming involved in a variety of development communication projects related to agriculture, non-formal education, health, etc., arising from the need to accelerate the circulation of Information at the Community level. These newly created media environments will all hopefully be submitted to anthropological scrutiny. All these are new activities that are being added to the established place of ethnographic film-making within the sub-discipline of Visual anthropology.

Yet the future of Visual anthropology depends not only on new ideas but also on new institutional developments such as the Granada Centre for Visual Anthropology. From my recent travels around Europe, (…), I have learned that the Manchester Centre is already being considered as a model institution to be replicated in several European countries. (…) One can only hope that this new setting, based on what some would once have regarded as an unholy alliance between academic institutions and television, will allow and provide for bold experimentation with new formats and styles, new ideas and new fields of enquiry, all so necessary to the future of Visual anthropology.”

(Auszug aus: Anthropology, Film and the Arctic People; !n:Anthropology Today; Vol. 5, No 2; April ’89, p. 4 - 10}