STAND AND DELIVER

USA 1988 | 104 Min. | 35 mm, OF

The dramatization of the life of an extremely demanding maths teacher at an East LA school in a Chicano neighbourhood: Thanks to his severity the pupils pass the exams and can go to college. The school authorities question the results as they don’t correspond with the usual failure figures. A fight against prejudice ensues.

»STAND AND DELIVER recounts the efforts of Bolivian-born Los Angeles resident Jaime Escalante to teach Advances Placement (A.P.) calculus to a predominantely Chicano group of students at East Los Angeles Garfield High School. Early in STAND AND DELIVER Jaime Escalante boosts his student’s confidence in their math abilities with a brief history lesson: ‘Did you know’, he says, ‘ that neither the Greeks nor the Romans were capable of using the concept of zero? It was your ancestors, the Mayas, who first contemplated the concept of zero, the absence of value. True story. You burros have math in your blood.’ A few scenes later he tells the same room full of students: ‘You already have two strikes against you. There are some people in this world who will assume that you know less than you do because of your name and your complexion. But math is the great equalizer’. STAND AND DELIVER thus establishes a tension between assimilation and maintaining an identity distinct from dominant culture. This tension finally erupts into conflict when the Educational Testing Service (ETS) suspects the students of cheating. Framing this suspicion as a flagrant case of institutional racism perpetrated by ETS, the film’s narrative illustrates the difficult relationships between an ethnic minority, in this case Chicanos, and a system that serves the so-called white minority (…)

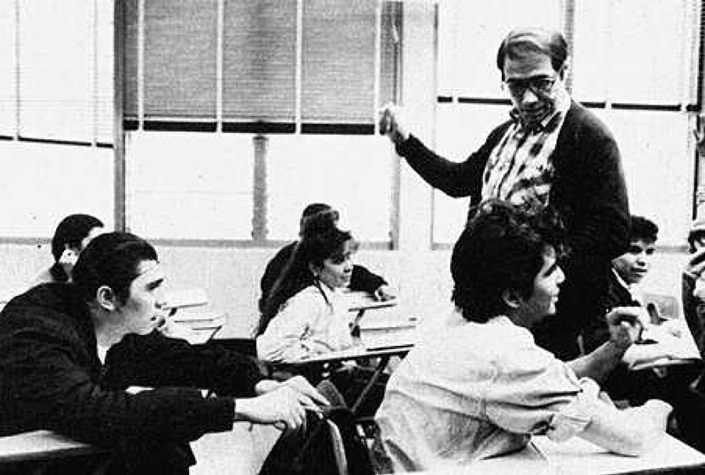

STAND AND DELIVER emphasizes the students’ and their teacher’s Latino heritage. The school system sees this ethnicity as an obstacle to learning, an attitude epitomized by the math department chair, Raquel Ortega. For Escalante, ethnicity provides an entrée into the students’ minds. By the end of the film, the students find strength in their Chicano identity and fight a system that would limit their opportunities because of that identity (…) Escalante hopes that A.P. calculus will prepare his students to enter a system that typically excludes Chicanos (…) In one of the first scenes Escalante enters a classroom full of chatting students. The chalkboard is decorated with graffiti as are the bulletin boards that surround the room. There are more students than chairs. Escalante discovers that a number of his students speak no English. Curtailed funding, graffiti, and language barriers situate Garfield as a barrio school, troubled from within by gang problems and vandalism, forsaken from without by the larger public education system. Escalante, the outsider, emerges as the force that reopens the path between the barrio and the larger world and that reestablishes communications between the students and the faculty. Escalante makes things happen because he is comfortable both in the barrio and in the system. The film highlights his ability to pass effortlessly between Chicano Los Angeles and a mixed, middle-class Los Angeles from the first moments. The title sequence begins with a full-screen image of moving water. As the camera pulls back the water appears to be a river and is finally revealed to be a duct in the middle of an urban area. A bridge crosses the duct, connecting two neighborhoods by allowing travel between them. Figuring Escalante’s border crossing, the next shot shows him driving across the bridge, leaving downtown Los Angeles. For the remainder of the credit sequence, the camera alternates between shots of Escalante passing through East Los Angeles and the neighborhood that Escalante sees as he drives. Escalante’s view establishes the ethnicity and socioeconomic status of the neighborhood -vendors selling fruit on the side of the road, calling out to cars in Spanish; store and truck signs in Spanish; Mariachi musicians carrying theirs instruments down the streets (…) Escalante’s border crossing is subtle. The significant border in STAND AND DELIVER does not separate two geopolitical entities. Nor is it a tangible physical border. Rather, it is the divide between socioeconomic classes and ethnic groups. Most people, particularly those on the priviledged side, avoid recognizing and discussiong this border. Racial and ethnic prejudice and cultural difference complicate travel across the border. STAND AND DELIVER shows how these problems are manifest within the barrio as well as in the larger scheme (…)

Escalante gives his students the tools he believes they need to qualify to enter the system. He takes them on a field trip to connect the classroon lessons to the real word. With this trip, Escalante escorts his students on their first border crossing (…) Border crossing represents the ultimate achievement – learning to balance one’s ethnic identity with the assimiliation requires to participate in the larger system (…)« Excerpts from ‘Crossing Invisible Boders: Ramón Menéndez’s STAND AND DELIVER’, Ilene S. Goldman in ‘The ethnic eye- Latino Media Arts’, 1996